This post is also available in:

Italiano (Italian)

Italiano (Italian)

Interview with Ilya Gringolts

on the occasion of the performance of

“Anahit” Poème lyrique dédié à Vénus

by Giacinto Scelsi

5 July 2024

opening concert of the tenth edition of the Chigiana International Festival & Summer Academy “Tracce” in Siena.

Gianni Trovalusci (President)

Alessandra Carlotta Pellegrini (Scientific director)

from Fondazione Isabella Scelsi

Maestro Gringolts, considering your dynamic and multifaceted artistic career, there are many questions we would like to ask you.

Starting from your interest and sensitivity to philological aspects, what, in your opinion, are the most significant aspects of performances based on historically informed interpretative practices?

For me, the charm of these performances has always been what we could consider “archaeological”, where the joy of the deepening process would, for example, involve comparing sources of the piece to understand its origins, meaning, etc. On the other hand, there is the desire and possibility of discovering something new, an unfamiliar approach, considering that it is impossible to reconstruct exactly the sound of the era… I consider Nikolaus Harnoncourt as the best example of reference for this approach: he uses historically informed performance practice rigorously but always to support his extremely original musical ideas.

You are dedicated to both early music and contemporary music, in addition to the great Romantic repertoire. What similarities and differences do you find in these seemingly distant practices regarding approach to the instrument and attitudes towards performance practice?

For me, classifications on this point are difficult to understand; there is only good music and less good music. My interest in contemporary music has almost always been present, as I studied composition as a child; obviously, all music that is performed is contemporary to its time. As for early music, I prefer to play it on period instruments, for ease; it works better! However, the attitude is always the same: finding and conveying the feelings, colors, and emotions hidden in the scores, whether it’s Bach or Lachenmann. It’s obvious that at the beginning, certain technical aspects need to be learned – that takes some time – but the final approach remains the same.

n 2020, you founded the I&I Foundation with Maestro Ilan Volkov, aimed at connecting composers, performers, and musical institutions to foster new commissions, especially for young composers, and engage a broader audience. Could you tell us about its inception and its importance to you in promoting and disseminating contemporary music?

The Foundation has done significant work, especially during the Covid period, generating over 20 pieces by various composers from around the world. Now, the main objective is to undertake larger projects – such as Mirela Ivičević’s violin concerto with a large orchestra titled “Überlala. Song of Million Paths” – and to continue supporting young and lesser-known composers.

What relationship do you think the audience of the new generations has with contemporary music?

I see room for improvement in how musical organizations are managed – there is a need for an increase in the percentage of contemporary music in programming. Promoters who have the confidence and determination to undertake this programming work usually have a direct and good relationship with the audience – after an initial period of adjustment. Conversely, promoters who remain conservative, sticking to the same repertoire, encounter difficulties when introducing new pieces which, due to lack of experience, are sometimes negatively received by the audience.

You have premiered new and important works by Peter Maxwell Davies, Beat Furrer, Michael Jarrell, Chaya Czernowin, Mirela Ivičević, and many others, including the world premiere of Salvatore Sciarrino’s “Sei nuovi capricci e un saluto” at the Chigiana International Festival 2023. In this broad context, how has the performer-composer-opera process developed?

I am fortunate to communicate with composers before, during, and after the process of creating a piece. This is how I learn about the emotions and thoughts behind the music, which I then try to rediscover in my interpretations. The flow of this process depends on the individual: some composers need creative exchange from the very beginning, almost “before birth,” while for others, it’s more important that it happens afterwards. The key thing is to keep the dialogue going.

Giacinto Scelsi and his sonic universe: is this your first encounter with it?

Absolutely yes, although I have always been a great admirer of Scelsi. Furthermore, I was able to follow the work process when my wife (whose name is actually Anahit!) was studying the piece for a concert that unfortunately never took place… Scelsi’s Quartets have also been on my bucket list for years!

What do you think about the music and the journey of such a unique author, with a distinctive profile in the history of 20th-century music?

It’s a very unique, almost parallel universe that is always aware of sound and its nature, its harmonics, the fascination of sound – in its simplest yet extremely complex foundation.

Anahit is a work that we consider lyrical and strong at the same time; what was your approach to this piece?

It’s a piece that celebrates the beauty, serenity, and purity of sound and its harmonics – but it also celebrates the monsters hidden within us! herefore, one must find the entire spectrum of colors, a wild rainbow so that the piece transforms into a sort of “out of body experience.”

What artistic and human qualities did it require you to bring to the forefront? What was your approach to the violinistic technique required for the performance?

The greatest challenge – but also the element that makes the piece (and many other pieces by the Maestro) so unique – is the scordatura. Here, it’s not just a matter of retuning the strings, but also replacing the D string with an A string, adding an extra level of brightness to the sonority of the piece. The tuning to G major completely changes the sound world and the instrument’s spectrum in an unpredictable way! Practical issues also revolve around the scordatura. he notation is perhaps the most demanding for me; only the resulting sounds are written down, not the actual notes that need to be played! Sometimes there are also aspects that are not particularly “violinistic” because, obviously, this was not a primary goal for the Maestro.

In Scelsi’s works, the title is, according to the author’s intentions, coherent with the image that takes shape within the piece, even though, as the Maestro himself stated, ‘Music speaks for itself.’ In this case, what did the relationship with Anahit, Poème lyrique dédié à Vénus, evoke in you?

The strength of this piece – and of all others in music – lies in the sonic colors of its material. This is ultimately its message, and the interpreter’s task is to communicate it.

1. Giacinto Scelsi in a photo from 1930s © Archivio Fondazione Isabella Scelsi. All rights reserved

2. Giacinto Scelsi’s instruments, in his house in Rome © Fondazione Isabella Scelsi. All rights reserved

3. I campanacci e Deva: Giacinto Scelsi’s instruments, above his piano © Fondazione Isabella Scelsi. All rights reserved

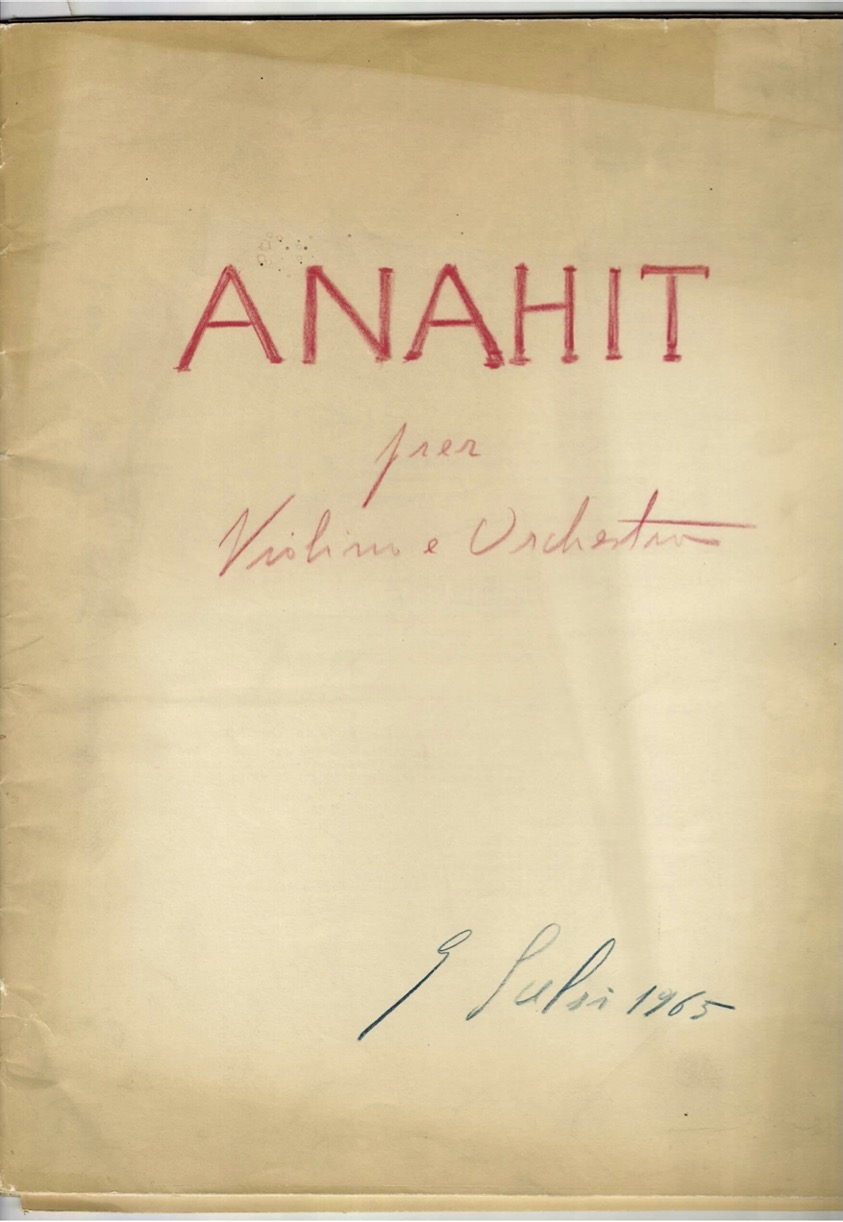

4. Frontispiece of Anahit © Archivio Fondazione Isabella Scelsi. All rights reserved

5. Detail from a list of works by Giacinto Scelsi © Archivio Fondazione Isabella Scelsi. All rights reserved

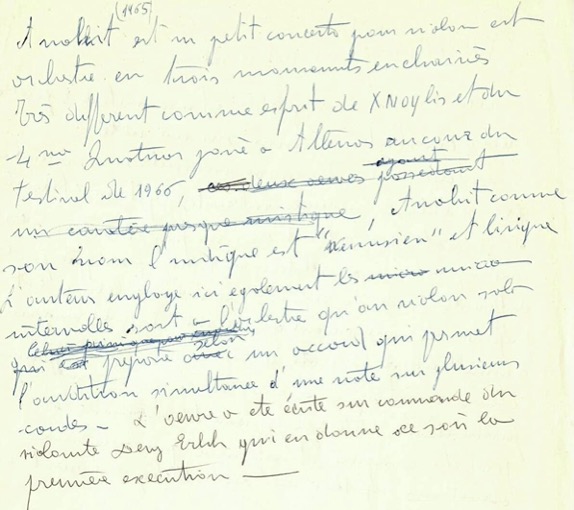

6. Small autograph about Anahit © Archivio Fondazione Isabella Scelsi. All rights reserved

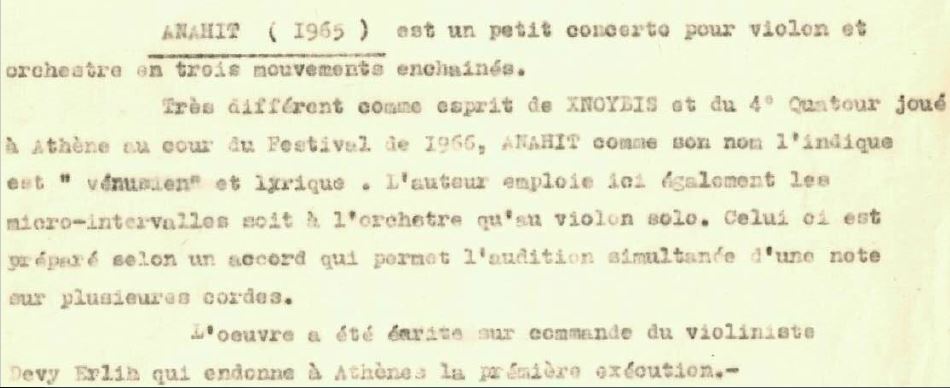

7. Typed note about Anahit © Archivio Fondazione Isabella Scelsi. All rights reserved